NES Emulator Debugging

Making an emulator for a 1980s game console is an exercise in reading and comprehension. The work is mostly translating documentation into code. It’s oddly satisfying, building a model of an ancient machine, instruction by instruction, device by device, especially once it can start running real programs. You end up with an appreciation for the capabilities (or lack thereof) of hardware at the time, and out of necessity, end up intimately familiar with the inner workings of a piece of computing history.

This post is not about making an emulator.

It is about the nightmarish, overwhelmingly complex, and at times seemingly hopeless task of hunting down the parts of your emulator that don’t behave exactly like the real hardware.

Let’s a-go!

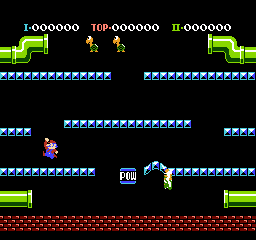

I’m making an emulator for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). To test my emulator, I run the game Mario Bros. When you start the game, it displays a menu for about 20 seconds, then runs a demo of gameplay. Once I had the CPU and video output working to the point that something not completely unintelligible was being rendered, I ran the game. I wasn’t emulating input yet, so I waited for the demo.

Hey, it mostly works!

There’s no gravity, Mario and Luigi look wrong, but only when they face to the right, and platforms get wider when you hit the bottom-left corner. These artifacts are the manifestation of emulator bugs that would take the better part of a month to find.

Debugging Printouts

The core of my debugging strategy is logging each instruction that is executed, and printing extra information

when something meaningful happens. In the case of the “no gravity” problem, I identified the address that stores

the vertical position of the first turtle (0x0368) to emerge from the pipe - the first character which gravity

should affect. The value it holds while the turtle is floating instead of

falling is 0x2C. Therefore at some point the game is writing0x2C to 0x0368 when it should be writing

something else, so I instrumented the emulator to print a message whenever 0x2C was read from any address in

memory, and also when address 0x0368 was written to.

Here’s a snippet of the output showing the Y position of the turtle being set to 0x2C.

I’ve annotated each instruction with a description of what it does.

CBDA Iny(Implied) increment index register Y

CBDB Inx(Implied) intrement index register X

CBDC Cpx(Immediate) 20 compare index register X to 0x20 (32)

CBDE Bne(Relative) F6 branch if X != 0x20 (true in this case)

CBD6 Lda(ZeroPageXIndexed) B0 load accumulator from address 0xB0 + X

reading 0x2C from 0xB8

CBD8 Sta(IndirectYIndexed) 14 store accumulator in [addess at 0x14] + Y

writing 0x2C to t1 y position

The non-human-readable lines are executed instructions. For example:

CBD6 Lda(ZeroPageXIndexed) B0

- Address of instruction:

0xCBD6 - Instruction:

Lda(load accumulator from memory) - Addressing Mode (ie. how to interpret the instruction argument):

ZeroPageXIndexed - Instruction Argument:

0xB0

The execution trace above is copying the turtle’s Y position from 0x00B8 to 0x0368.

The Lda instruction reads a value from memory into a CPU register called the “accumulator”.

The Sta instruction stores the accumulator in memory. This is part of a loop that transfers

data from the “zero page” - the first 256 bytes of memory - into other parts of memory.

Most instructions have special variants (e.g. Lda(ZeroPageXIndexed) which can only access the zero page,

but take up less memory and execute faster.

It seems that Mario Bros. uses the zero page

for function arguments and return values, and other temporary intra-frame storage.

The 0xB0 address read from above is, at other points in the execution, used to store the

Y position of other characters. For inter-frame storage of character data, address in

0x0300 - 0x0400 seem to be used.

This code is probably transferring the result of some computation into longer-term memory.

This indicates that the problem happened earlier in the frame.

To find details of what is done to the Y position while it’s in 0x00B8,

we could instrument the emulator to print whenever 0x2C is read from this new address.

C750 Jsr(Absolute) CC90 call function at 0xCC90

CC90 Lda(ZeroPage) B8 load value at 0xB8 into accumulator

reading 0x2C from 0xB8

CC92 Clc(Implied) clear carry flag

CC93 Adc(Immediate) 08 add 8 to the value in accumulator

CC95 Cmp(Immediate) E4 compare accumulator to 0xE4

CC97 Bcc(Relative) 08 branch if accumulator < 0xE4 (true)

CCA1 Sta(ZeroPage) 01 store accumulator at address 0x01

CCA3 Lda(ZeroPage) B9 load accumulator with value from address 0xB9

CCA5 Sta(ZeroPage) 00 store accumulator at address 0x00

CCA7 Jsr(Absolute) CA9A call function at 0xCA9A

This code is reading the turtle Y position from 0xB8, adding 8 to it, and storing the result in address 0x0001. The Y coordinate increases moving down the screen, so at first I thought that adding to the turtle’s Y position was gravity at work, but this will turn out to be incorrect.

What are we searching for?

The debugging process so far has closely resembled how we might debug Mario Bros. - the program being run on the emulator - without access to its source code. We’re trying to find the part of the program that applies gravity to characters because it looks like something is wrong with gravity. Of course, we know that the program we’re running is fine! Run it on someone else’s emulator, or real NES, and gravity works.

And this is the crux of why debugging an emulator is hard. The layer of abstraction where the problem manifests is never the layer of abstraction where we’ll find the problem. The problem “gravity is not working” is a symptom of a problem that has nothing to do with gravity. One or more instructions is being interpreted incorrectly, and these instructions happen to be used by the game at some point to apply gravity.

If we were to look at the code that applies gravity in Mario Bros., we would find that there is nothing wrong with it. Our best bet would be to look at a trace of this code being run (what we’ve been doing so far) with enough detail logged such that when a broken instruction is executed, the update to the machine state won’t match our expectations. Of course the instruction emulation is based on my interpretation of the CPU manual, so it’s likely that my expectations themselves are incorrect.

Since the virtual hardware, and my expectations of how the hardware should behave may both be faulty, the only real “source of truth” we can rely on is the software running on the emulator. This is an interesting reversal of the usual assumptions - one typically assumes that their hardware works as expected and all bugs are problems with software. We’ll trace the execution of Mario Bros., and if it looks like the game is doing something that doesn’t make sense, that might indicate that the emulator is behaving differently than the real hardware would.

Fixing a (hopefully!) simpler problem

I spent a few days pouring over execution traces trying to find where gravity was applied and the bug which prevent it from working. Eventually I decided to take a break and work on what was hopefully a simpler problem.

The Mario and Luigi sprites are a 2x3 rectangle of 8 pixel square tiles. When they face to the right, both columns are drawn overlapping instead of adjacent.

It’s supposed to look like this.

NES Sprite Rendering

To get to the bottom of this, we need to know a little about how rendering works on the NES. The NES Picture Processing Unit (PPU) can render up to 64 8x8 pixel foreground sprite tiles at a time. Backgrounds are rendered differently, but aren’t important for finding this bug. To render a sprite tile, the game writes a 4-byte description of the tile to a special region of memory called the Object Attribute Memory (OAM). This description contains the position of the tile on the screen, a tile index specifying which tile to render, and some attributes to fine-tune rendering.

OAM is not addressable directly by the CPU. Instead, the CPU writes a copy of

what it wants OAM to contain into RAM, starting at a 256-byte aligned address (ie. an

address whose low byte is 0), then writes the high byte of this address to a PPU

register named OAM DMA. Writing to OAM DMA causes the PPU to directly read the

256 bytes starting at specified address, and upload it to OAM.

Finding the Mario Sprite

By logging writes to OAM DMA, I found that the only value Mario Bros. ever

writes to it is 2. This means that it’s storing sprite data in the region of

RAM at 0x0200 - 0x02FF.

Next we need to find out which part of OAM contains the description of the Mario

tiles. Each sprite tile is described with a 4-byte data structure. The 4th byte

of this structure contains the X coordinate of the tile. By logging the X

coordinate of each tile every frame and watching how they change as Mario moves

on the screen, I identified the 6 OAM entries corresponding to Mario as those

occupying 0x0210 - 0x0227 (24 bytes = 6 tiles * 4 bytes per tile)

prior to uploading.

I instrumented the emulator to log writes to 0x0213 and 0x0217 which

should correspond to the X positions of the top 2 tiles of Mario.

I found a single loop where one iteration wrote to 0x0213, and another

iteration wrote to 0x0217.

CC20 Inx(Implied)

CC21 Lda(IndirectYIndexed) 12

CC23 Bit(ZeroPage) B7

CC25 Bvs(Relative) 03 branch if overflow flag is set

CC2A Eor(Immediate) FF

CC2C Sec(Implied)

CC2D Sbc(Immediate) 08 subtract 8 from the accumulator

CC2F Sec(Implied)

CC30 Adc(ZeroPage) B9

CC32 Iny(Implied)

CC33 Sta(AbsoluteXIndexed) 0200

writing 0x68 to 0x0213

...

CC20 Inx(Implied)

CC21 Lda(IndirectYIndexed) 12

CC23 Bit(ZeroPage) B7

CC25 Bvs(Relative) 03 branch if overflow flag is set

CC27 Clc(Implied)

CC28 Bcc(Relative) 06

CC30 Adc(ZeroPage) B9

CC32 Iny(Implied)

CC33 Sta(AbsoluteXIndexed) 0200

writing 0x68 to 0x0217

A Hunch

These two iterations look slightly different. Notice that in the 0x0213

iteration (the first iteration) 8 is subtracted from the accumulator

(instruction address

0xCC2D), and in

the 0x0217 iteration, this subtraction is skipped. 8 happens to be the

width of a sprite tile in pixels. If this subtraction occurred in the latter

iteration, it would have written 0x60 instead of 0x68 to OAM, and the left

half of the sprite would be shifted 8 pixels to the left and would no longer overlap

with the right half (note that this assumes that the former iteration is the

top-right tile, and the latter one is the top-left tile).

The first point where the two iterations differ is the Bvs instruction

at address 0xCC25. This instruction branches by a specified offset if the

“overflow” flag is set. This branch is taken in the first iteration (note the

change in instruction address after Bvs executes), and not

taken in the second iteration.

Arithmetic operations set the overflow flag when a

signed integer overflow occurs. The fact that this code executes the Bit

instruction, and then branches based on the overflow flag’s value, suggests that

Bit sets and clears the overflow flag too.

My emulator was updating the

overflow flag when emulating Bit, but I double checked the manual at this

point just to be safe.

The Bit instruction computes the bitwise AND of a value from memory and the

accumulator, discarding the result, and setting some status register flags.

Here’s what the MOS6502 Programmer’s Manual has to say about the status register

flags set by Bit:

The bit instruction affects the N (negative) flag with N being set to the value of bit 7 of the memory being tested, the V (overflow) flag with V being set equal to bit 6 of the memory being tested and Z (zero) being set by the result of the AND operation between the accumulator and the memory if the result is Zero, Z is reset otherwise. It does not affect the accumulator.

Bit is unusual because it

sets the overflow (V) and negative (N) flags based on its argument, instead of

its result. Every other instruction that updates the overflow and negative flags does so

based on its result.

In my first pass through the manual I did not pick up on this subtlety!

Correcting this instruction in my emulator, and now Mario renders correctly.

It seems that fixing this bug also fixed gravity…

Great!

Platforms get wider when you jump into them

Look closely at the previous recording. Luigi jumps and hits the ceiling, and the platform seems to grow a little wider as a result. This is not supposed to happen!

To help debug this, I implemented input emulation so I could actually play the game and conduct experiments.

Here’s a more explicit demonstration of the problem.

This only happens if you hit a platform on its bottom-left corner. This fact, coupled with the turtle falling through the floor suggests that this bug relates to collision detection. In Mario Bros., when you hit a platform from underneath, an animation plays where the platform bulges above you, damaging any enemies standing on that part of the platform. There is an emulator bug with the symptom that collision detection with platforms has a lateral offset, which means that if you jump just to the left of a platform, the game thinks you hit the platform from beneath. Because it thinks you hit a platform from beneath, the game plays the platform bulge animation above the character, which leaves a fresh platform where there was none before. This new platform can now be collided with in the same way allowing it to grow even further to the left.

If collision detection has an erroneous offset, you should be able to move through the right-hand side of a platform too.

Turtles also fall through platforms too early on the right-hand side, and too late on the left-hand side.

Function Analysis

Collision detection is complicated, and after a few days of blindly staring at

execution traces I elected to take a step back and try to get a better

understanding of how the game works. To that end I wrote a little library for

exploring function definitions in NES programs. The NES CPU has an instruction

named JSR (Jump SubRoutine) which pushes the current program counter on the

stack, and moves execution to a specified address. A second instruction, RTS

(Return from SubRoutine) pops an address from the stack and moves execution to

that address. Respectively, these instructions are used to call and return from

functions.

To find all the functions in the program, my library scans the ROM for all

instances of the JSR instruction, looking at its argument to find addresses

where functions begin. To find out where a given function ends, step through the

function instruction by instruction, stopping when a RTS instruction is

reached. Upon encountering a conditional branch, we need to account for the case

when the condition is true, and when the condition is false. I use a stack (the

data structure) to keep track of execution paths yet to be explored.

Instructions that unconditionally change the program counter are followed,

with the exception of JSR (we’re only exploring the current function - not

the functions it calls) and RTS, which indicates we should stop exploring the

current branch. Keep track of the addresses that have been explored in this

traversal and stop if an instruction would change the program counter to

somewhere we’ve already been.

This is effectively a depth-first search through the control flow graph of the

function.

Here’s a trace of a simple function.

0xCDD1 Pha(Implied) ;; save accumulator onto stack

0xCDD2 Clc(Implied) ;; clear the carry flag

0xCDD3 Lda(ZeroPage) 0x14 ;; load value at address 0x14 into accumulator

0xCDD5 Adc(ZeroPage) 0x12 ;; add value at address 0x12 to accumulator

0xCDD7 Sta(ZeroPage) 0x14 ;; store accumulator at address 0x14

0xCDD9 Lda(ZeroPage) 0x15 ;; load value at address 0x15 into accumulator

0xCDDB Adc(ZeroPage) 0x13 ;; add value at address 0x13 to accumulator

0xCDDD Sta(ZeroPage) 0x15 ;; store accumulator at address 0x15

0xCDDF Pla(Implied) ;; restore accumulator from stack

0xCDE0 Rts(Implied) ;; return

What is this function doing?

It adds the byte at address 0x14 with the byte at address 0x12, storing the

result at address 0x14, then adds the byte at 0x15 with the byte at 0x13,

storing the result in 0x15. Notice the carry flag is cleared once at the

start, and then not cleared in between the two additions. The ADC instruction

adds the carry flag to its result, and sets the carry flag if the result of the

addition is greater than 255 (the maximum value that fits in a byte).

This function treats the 2 bytes at 0x14 and 0x15 as a single 2-byte

little-endian

integer, and likewise for the 2 bytes at 0x12 and 0x13. This function adds

these two 16-bit integers, and returns the result. We can interpret

0x12 - 0x15 as containing function’s arguments. Similarly, we can interpret

0x14 - 0x15 as containing the function’s return value (after the function

returns).

Here’s how you might write this function in rust:

fn add16(a: u16, b: u16) -> u16 {

a + b

}

The function calling convention Mario Bros. seems to use is to choose a range

of addresses in the zero page (0x0000 - 0x00FF) for each function, and to

store the function’s arguments and return value in this range. Each function

seems to use unique addresses for its arguments and return values, which would

allow one function to call another function without the first function needing

to worry about its own arguments being overwritten by some later function.

Note that this calling convention does not support recursion,

as the second nested call of a function would overwrite the arguments from

the first call.

Function analysis didn’t directly help solve my problem, but it did help get a better understanding of what the program was trying to do.

A Mysterious Function

Much like before, I started by inspecting the memory of the running game to find

out which address contained Mario’s X and Y coordinates between frames. Tracing

load and store instructions involving these addresses led me to the following function, which was being

passed Mario’s X and Y coordinates through zero page addresses 0x00 and

0x01.

;; Load coord_x into accumulator.

CA9A Lda(ZeroPage) 00

;; Right-shift the accumulator by 1 bit 3 times, effectively dividing it by 8.

CA9C Lsr(Accumulator)

CA9D Lsr(Accumulator)

CA9E Lsr(Accumulator)

;; Store the accumulator [coord_x / 8] in address 0x12.

CA9F Sta(ZeroPage) 12

;; Store the value 0x20 in address 0x13.

;; The 2 bytes at 0x12-0x13 now represent a 16-bit integer

;; whose value is [0x2000 + (coord_x / 8)].

;; This is because 0x20 is the high byte, and [coord_x / 8] is the low byte.

CAA1 Lda(Immediate) 20

CAA3 Sta(ZeroPage) 13

;; Store a 0 at address 0x15.

CAA5 Lda(Immediate) 00

CAA7 Sta(ZeroPage) 15

;; Load coord_y into accumulator.

CAA9 Lda(ZeroPage) 01

;; Bitwise AND the accumulator with 0xF8.

;; 0xF8 in binary is 11111000, so this clears the low 3 bits of coord_y.

;; This effectively rounds coord_y down to the next lowest multiple of 8.

CAAB And(Immediate) F8

;; Left-shift the accumulator, setting the carry flag to the most-significant

;; bit of the accumulator prior to this instruction executing.

;; Then left-rotate the value in address 0x15 (explicitly set to 0 above).

;; Left-rotating is the same as left-shifting, except the least-significant

;; bit of the result is set to the carry flag's current value, and then the

;; carry flag is set to the original most-significant bit (ie. it rotates

;; "through" the carry flag).

;;

;; This doubles the value in the accumulator. If twice the value of the

;; accumulator is too large to fit in the 8-bit accumulator register, the

;; overflowing bits are stored in the low bits of address 0x15.

CAAD Asl(Accumulator)

CAAE Rol(ZeroPage) 15

;; Repeat the above, doubling the accumulator a second time.

CAB0 Asl(Accumulator)

CAB1 Rol(ZeroPage) 15

;; Store the accumulator in address 0x14.

;; At this point, the little-endian 16-bit integer at 0x14-0x15 is

;; coord_y rounded down to the next multiple of 8, then multiplied

;; by 4.

CAB3 Sta(ZeroPage) 14

;; Call the add16 function defined above.

;; Once this function returns, the sum of the 16-bit integer at 0x12

;; and the 16-bit integer at 0x14 ends up in 0x14-0x15.

CAB5 Jsr(Absolute) CDD1

;; Copy the result of add16 into the return value address of this function.

;; This function will return the 16-bit integer returned by add16

CAB8 Lda(ZeroPage) 15

CABA Sta(ZeroPage) 00

CABC Lda(ZeroPage) 14

CABE Sta(ZeroPage) 01

;; Return.

CAC0 Rts(Implied)

Phew!

Just what is going on here?

The first hint is that coord_x is divided by 8. 8 happens to be the width and

height of a

sprite tile in pixels. Dividing the X pixel coordinate by 8 translates it into

a tile coordinate. If X is being translated into tile space, it seems sensible

to also translate the Y coordinate, but this Y coordinate translation is not so

straightforward.

The And(Immediate) F8 instruction holds

the key. This rounds the Y coordinate down to the next multiple of 8, which is

equivalent to dividing Y by 8, rounding down, and then multiplying the result

by 8. The result of this operation is then multiplied by 4 (left-shifting twice),

so the final result for Y is ((coord_y / 8 ) * 8) * 4 = (coord_y / 8) * 32 (assuming integer division).

The second hint is that the NES video output is 256 pixels wide = 8 pixels per tile * 32 tiles. The width of the screen is 32 tiles.

The rust code with the same intent as the above assembly would be:

// don't forget about the 0x2000 which is added to X after dividing by 8

const MYSTERIOUS_OFFSET: u16 = 0x2000;

const TILE_SIZE_PIXELS: u8 = 8;

const SCREEN_WIDTH_TILES: u16 = 32;

fn mystery(pixel_coord_x: u8, pixel_coord_y: u8) -> u16 {

let tile_coord_x = (pixel_coord_x / TILE_SIZE_PIXELS) as u16;

let tile_coord_y = (pixel_coord_y / TILE_SIZE_PIXELS) as u16;

let index = tile_coord_x + (tile_coord_y * SCREEN_WIDTH_TILES);

return index + MYSTERIOUS_OFFSET;

}

If we treat the 32x30 (NES video output is 240 pixels = 30 tiles high)

tiles on the screen as a 1D array of tiles ordered

left-to-right, then top-to-bottom, then this function computes the index of the

tile containing Mario’s coordinate. And then it adds 0x2000. How mysterious.

When this function is called with Mario’s coordinates, the result is stored

in 0x0520-0x0521. Later in the frame, these addresses are read:

CB87 Lda(AbsoluteXIndexed) 0520

CB8A Sta(Absolute) 2006

CB8D Inx(Implied)

CB8E Lda(AbsoluteXIndexed) 0520

CB91 Sta(Absolute) 2006

CB94 Lda(Absolute) 2007

CB97 Lda(Absolute) 2007

The above code is run in a loop several times each frame. The addresses 0x2006 and 0x2007

contain Picture Processing Unit (PPU) registers. Thus, I assumed that this code is

somehow related to rendering. Not collision detection. So I moved on to look

elsewhere.

Execution Trace Diffing

What is the difference between a frame with a Mario collision, and a frame without? To get to the bottom of collision detection, I came up with an experiment to find out how execution differs between a frame where Mario collides with the ceiling, and a frame where he does not.

I recorded a save state mid-jump, and instrumented my emulator to load the save and overwrite Mario’s X position with a specific value which won’t result in a collision.

Notice how Mario teleports a few pixels to the left on the second frame.

I ran this for a specific number of frames, and recorded an execution trace. Then I repeated the experiment with an X offset which would result in a collision.

Equipped with a collision trace, and a non-collision trace, I could now compare the two. Since there’s a discrete difference in the program’s behaviour between the two traces, it stands to reason that there will be at least one branch instruction where one instance branches, and the other does not. The first such branch instruction will hopefully tell me something about how this game does collision detection.

In addition to the instructions being executed, I also logged several other data

which I thought would be useful, such as the value read by the LDA (load

accumulator from memory) instruction.

In these diffs, the black lines are in both traces, the “-” (red) lines are only in the collision trace, and the “+” (green) lines are only in the non-collision trace.

As expected, during the first few frames where no collision occurs, the only difference

was the result of the Mario X position being different between traces. The first

difference in the diff snippet below is clearly an example of this, as the

values 0xB2 and 0xB3 differ by 1.

@@ -40592,12 +40592,12 @@ LDA read value 22

CB8A Sta(Absolute) 2006

CB8D Inx(Implied)

CB8E Lda(AbsoluteXIndexed) 0520

-LDA read value B3

+LDA read value B2

CB91 Sta(Absolute) 2006

CB94 Lda(Absolute) 2007

LDA read value 24

CB97 Lda(Absolute) 2007

-LDA read value 93

+LDA read value 24

CB9A Sta(AbsoluteXIndexed) 0520

CB9D Inx(Implied)

CB9E Dey(Implied)

The second difference is more interesting. 0x93 vs 0x24? And look at those

instruction addresses. We’ve been here before! This is the code that reads from

the result of the mysterious index-computing function from the previous section.

A bit further down the diff, we see the first instance of a branch instruction

that is followed in one trace but not the other. The CAC3 Bcc(Relative) 0E

instruction has this honour. This instruction, and the Cmp instruction which

precedes it, compare the accumulator to the immediate value 0x92, and branch if

the accumulator is less than 0x92. In the collision case (red), the branch was

not followed. The preceding LDA indicates that in this case the accumulator

contained 0x93. In the no-collision case (green) the branch was followed as the

accumulator contained 0x24.

@@ -41963,193 +41963,22 @@ LDA read value 1

C97F And(Immediate) 0F

C981 Beq(Relative) 09

C983 Lda(ZeroPage) CB

-LDA read value 93

+LDA read value 24

C985 Jsr(Absolute) CAC1

CAC1 Cmp(Immediate) 92

CAC3 Bcc(Relative) 0E

-CAC5 Cmp(Immediate) A0

-CAC7 Bcc(Relative) 07

-CAD0 Lda(Immediate) 01

-LDA read value 1

-CAD2 Rts(Implied)

+CAD3 Lda(Immediate) 00

+LDA read value 0

+CAD5 Rts(Implied)

C988 Ora(Immediate) 00

C98A Bne(Relative) 04

The values 0x24 and 0x93 have something to do with graphics, as they are read

in the part of the program that interacts with the Picture Processing Unit

(remember addresses 0x2006 and 0x2007 refer to PPU registers), and they probably

have something to do with collision detection, as the first differing branch

between the two traces was because of these two values.

Let’s hazard a guess that these are indices of background tiles.

Tile number 0x24:

That is an 8x8 square of black pixels, used for the empty space in the background.

Can you guess what tile 0x93 is:

A floor tile!

All the other solid tiles have indices greater than 0x92 as well.

The comparison with 0x92 is this game’s way of checking if an area of the screen

is solid.

Recall that the problem we’re trying to solve is that collision detection seems to be off some value. Let’s assume for a second that this value is 8 pixels, or 1 tile. An off-by-one error in the function that computes the tile index seems like the obvious culprit, but I checked the arguments and return value of this function in my trace and it definitely was working as intended.

The PPU: More than just rendering!

The diff revealed something interesting going on in the code from earlier which I dismissed as related to rendering. Before diving back in, here’s all you need to know about the NES Picture Processing Unit.

This code is interacting with 2 PPU registers, mapped to 0x2006 and 0x2007.

0x2006 refers to the “PPU Address” register. Not unlike modern computers, the

NES had a dedicated memory attached to its graphics hardware. This video memory

could not be addressed directly by the CPU. If the CPU wishes to read or write

from video memory, it must write the low byte of the 2-byte video memory address to 0x2006, and then

write the high byte of the address to 0x2006.

Once the CPU has written both bytes of the address to 0x2006, it can read or

write 0x2007, the “PPU Data” register, to access video memory at the specified

address. The PPU keeps

track of the “current” address being accessed, and increments this address after

each access. Thus if you wished to write 16 consecutive bytes to video memory,

you would first write the intended video memory address to 0x2006, and then

write to 0x2007 16 times.

Here’s the trace:

;; Assume that the X index register is initially 0,

;; so the first 2 LDAs read from 0x520 and 0x521.

;; Also assume that 0x0520 contains the low byte of

;; the tile index computed by the mysterious function,

;; and 0x0521 contains the high byte.

;; Write the low byte of the mysterious function output

;; to the PPU Address Register.

CB87 Lda(AbsoluteXIndexed) 0520

CB8A Sta(Absolute) 2006

;; Write the high byte of the mysterious function output

;; to the PPU Address Register.

CB8D Inx(Implied)

CB8E Lda(AbsoluteXIndexed) 0520

CB91 Sta(Absolute) 2006

;; Load accumulator from PPU Data Register.

CB94 Lda(Absolute) 2007

;; Load accumulator from PPU Data Register again.

;; The value loaded here is the one that later gets compared

;; with 0x92 to see if the tile is solid.

CB97 Lda(Absolute) 2007

This code takes the output of the mysterious index + offset function detailed

above, and reads the byte from video memory at that address. It then discards

this value, overwriting it with the byte read from the next video memory

address. This second byte is then compared with 0x92 to check if a collision

occurred.

This explains what the mysterious offset, 0x2000, is for. In the NES video

memory layout, 0x2000 is the address of the start of the first “nametable” - an

array of tile indices that specify the background tiles to render. The

mysterious function computes an offset within this array, and then adds it to

the video memory address of the start of the array.

One mystery solved!

This also explains how character/level collision detection worked in Mario Bros. To test if an area of the screen is solid, determine the tile currently rendered there by reading from video memory, and check if it’s one of the solid tiles. That’s why rendering the floor bulge animation resulted in a solid floor remaining in the game world. If you can see it, you can collide with it.

The last two lines of the trace above (both Lda(Absolute) 2007) made me highly

suspicious. The index computation seemed to be doing something sensible, and

getting the correct result. The tile index read by the first of these two

instructions should be the tile used for collision detection decisions. Why

then, is the first-read value being discarded and replaced with the index of the tile one space to

the right?

Making an emulator for a 1980s game console is an exercise in reading and comprehension.

An excerpt from the nesdev wiki that I overlooked when first reading about the PPU:

When reading while the VRAM address is in the range 0-$3EFF (i.e., before the palettes), the read will return the contents of an internal read buffer. This internal buffer is updated only when reading PPUDATA, and so is preserved across frames. After the CPU reads and gets the contents of the internal buffer, the PPU will immediately update the internal buffer with the byte at the current VRAM address. Thus, after setting the VRAM address, one should first read this register and discard the result.

Now that I’ve had my fun, I’m going to subject my emulator to a suite of test ROMs to clean up any not-yet manifested bugs. There’s still a lot of work to do before my emulator is finished. At the moment there’s no sound, many PPU features are unimplemented, and only the most basic cartridges are supported.

You can view the source code for my emulator here.